The Problem With Average Solutions

Eugen Eşanu

Designer and casual writer. Currently building Shosho.co.

And Other Issues Between

This article originally appeared on UXPlanet.

A couple of years ago, WordPress had a security flaw, and once they fixed it, they asked all their users and customers to update to the newest version. Unfortunately, many people didn’t want to. After the WordPress team gave it some thought, they came up with an unusual solution. During their next email update, they said they introduced five new emojis. And their users began updating the app.

We humans tend to notice things which are weird and not the ones which come as normal or usual. It is because evolution trained us to notice the unusual so we can survive in unknown situations.

If you are following and believing in the standard thought of the school of economics, you have the idea that every transaction around us is done based on full trust and clarity. You think that people know exactly what they want, and every transaction is done with perfect use of information. If you are one of those people, you may also tend to believe that marketing, advertising or even design shouldn’t exist or be used in business. This way, you see those fields as a cost to be minimised and not spent on. And not as a source of value creation.

Value is subjective. It can be created or destroyed as much as you describe it by what it is.

We don’t live in a world where we all know what we want and how much we should pay for something. Once I was searching for an apartment to rent on different websites, and I found one that costs around 1k a month. The apartment looked modern with a view through the window towards the road and some beautifully decorated restaurants. But the apartments from the other side of the building had a view towards a canal. It was about 1.9k a month to rent. It is a similar apartment, same structure and size, except the view. You essentially pay 400 more to have a better view and see the sunset each evening. To some, it may come as a rip-off but to others as value.

If you did an MBA or something similar, it changes your way of looking at the world. You assume that people already know what they want and what they are prepared to pay for it. And because of it, you also tend to believe they are ready to buy the product at the lowest cost possible. This type of thinking will drive you when making business decisions, to dedicate all your time and resources to improving efficiency, rather than increasing or finding opportunities.

In our attempt to rationalise the world we might make it worse — Rory Sutherland

Business is more an “ecosystem” than a process. Where various parts handle the creation of the outcome. Design, marketing, sales, advertising, logistics and others. And all are glued with behavioural economics. Human beings are emotional, not logical. We have our behaviour ingrained by evolution and changed the top by modern society.

What you should understand is that value is created by many factors, not only by minimising a cost. For example, in a restaurant, the value is created by the person who cooks the meal and the person who cleans the floors. In the same way, you can have a Michelin-star restaurant, with the best food possible, but it smells awful inside, and nobody will enjoy it. But we tend to not apply such thinking to building products and services. We sometimes tend to build an excellent product, but don’t communicate or market it accordingly. Or position it in the right way. This way you can lose a potential million for your business.

It is same way some scientists refuse to use philosophy in their work as they rely purely on logic, meanwhile life is never logical.

How Big Data Lies to You

Tricia Wang was the person responsible for recommending Nokia to launch a smartphone when it was still in the early days. She is a tech ethnographer, and in one of her Ted Talks, demystified big data and identified its pitfalls, she suggests that we should focus instead on “thick data” — valuable, unquantifiable insights from actual people — to make the right business decisions and thrive in the unknown.

Tricia lived among the Chinese people for many years and conducted ethnographic work. And by living with migrants and in internet cafes, to working as a street vendor, she gathered lots of indicators that led her to conclude that even low-income consumers were ready to pay a high price only to have an expensive smartphone.

When she was working for Nokia, with all her efforts, she tried to convince and prove to them that they need to build a smartphone. But they declined it. Why? Because their Big Data showed an enormous amount of evidence that people are not ready to spend a lot of money on a smartphone. Nokia wanted to wait until the day they would be cheap enough so anyone can afford them. Because why would someone spend $900 on a phone?

But the real-life examples are different. People don’t mind spending around 1k for a phone. Because value is subjective and humans are not rational. In this case, you prefer status and possibilities rather than efficiency.

So why didn’t they spot this during their research and interviews with customers? When you ask people — “Would you pay 1k for a phone with Internet access and other features?” — it is hard for them to imagine how great it would be. Or what possibilities it can bring. At that time (2007–08) when you were asked about a smartphone, all you had in mind is that it’s a phone on which you can send text messages, call and play snake.

But once you present that new product in front of them, everything changes. You couldn’t imagine how a smartphone would change your life because you never saw it. People don’t know until they see and use it. And what happens today? People are even willing to borrow money only to get a smartphone. Humans are unpredictably predictable.

All big data suffers from the same problem: it comes from the past. But as much history as we have, we never learn our lessons. It is hard and almost impossible to predict or create the future with past data. You can only adapt to it.

To build your map of the world on current data you have is a dangerous thing to do.

Another issue here is that people at the top tend to have only a general view of how their business works. And we also tend to believe that more data is better information. But 1+1 does not always equal 2. The more data you have, the more it increases the chances of not spotting an opportunity. Or even worse, making the wrong decision about your product or service. The real information might be at the extreme or fringes. Data gives you a general view, but never a general view of your customer, persona, or solution. There are always extremes of possibilities.

The middle is not always the best approach. In the same way, a person who is at the reception might know better why the process of accepting new customers is slow, rather than a manager who never works there.

There might be a gap in the market, but is there a market in the gap?— Rory Sutherland

People become so fixated on numbers or on quantifying things, that they can’t see anything outside. Even when you show them clear evidence. So quantifying is addictive, and when we don’t have something to keep that in check, it’s easy to fall into a trap. Meanwhile, you are searching for future you are trying to predict in a haystack, you don’t feel or see the tornado that is coming behind your back.

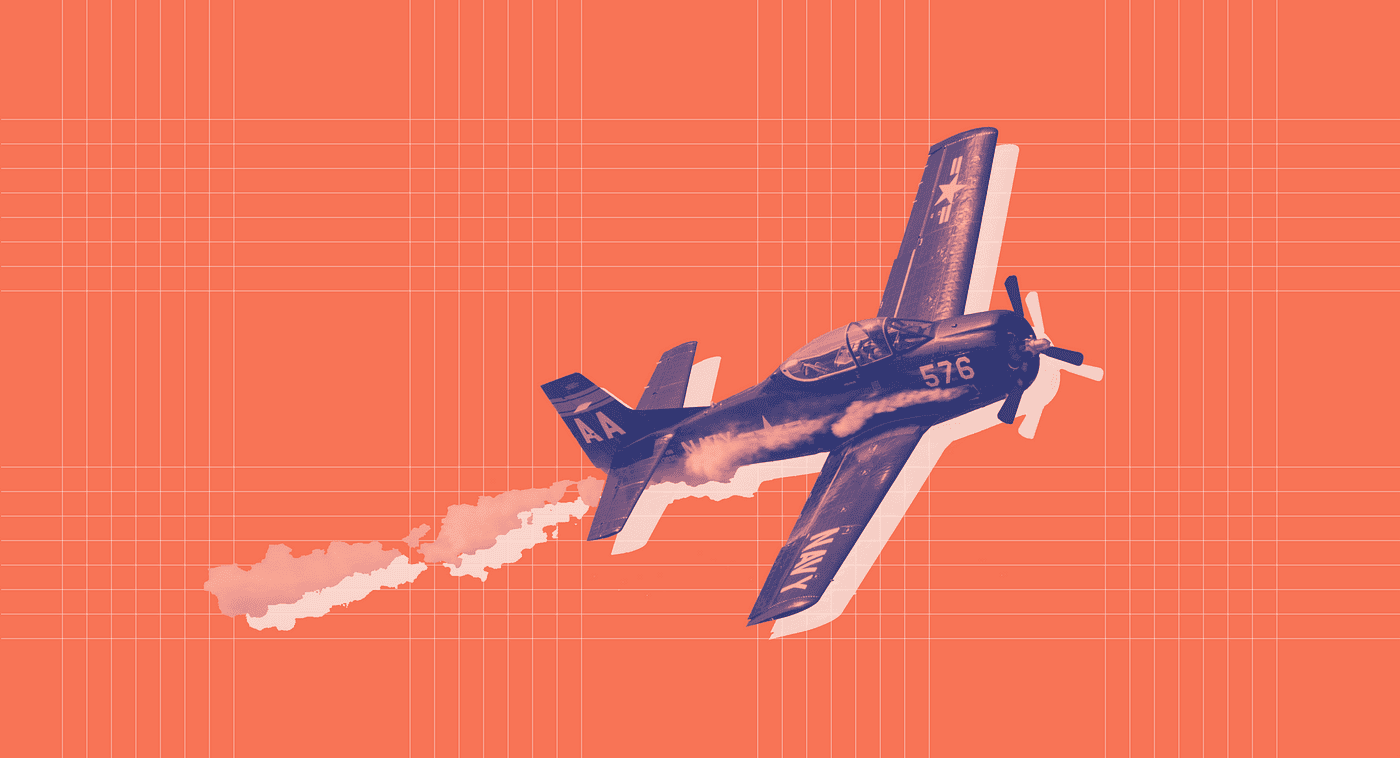

The Cockpit of a Plane

The middle market might not even exist. As you can notice, solutions and opportunities are always at the extreme. For example, when you design the cockpit of a plane, you will realise there is no average body type. The number of people who are on the average side is small. So you can easily get misled by the average.

In the late 1940s, the United States air force had a serious problem: its pilots could not keep control of their planes. Although this was the dawn of jet-powered aviation and the planes were faster and more complicated to fly, the problems with planes were so frequent that the air force had an alarming, life-or-death mystery on its hands.

“It was a difficult time to be flying. You never knew if you were going to end up in the dirt.” At its worst point, 17 pilots crashed in a single day.”-The End of Average

At that time, commanders thought it was a “pilot error”. The judgement seemed reasonable. But the engineers determined it wasn’t the pilot's fault. They were sure their skills were beyond good. After many attempts at finding the issue, they turned their attention to the cockpit itself.

Back in 1926 when the first designs of the plane were made, the pilot seat was standardized. The engineers measured the body of hundreds of pilots and used the average of that data to make the cockpit. In years to come, seats, distance to the pedals, helmet shape and everything else were based on the first standardized set in 1926. But in 1950 they tried again to measure all body types and create a new standard design, which should reduce the number of crashes. It didn’t help either.

But there was one recruit, a 23-year-old scientist who had doubts about it — Lt. Gilbert S. Daniels. The Aero Medical Laboratory hired Daniels because he had majored in physical anthropology, a field that specialized in the anatomy of humans.

In one of his studies, he compared the hands of 250 pilots. He tried to connect them to the body type of a person. But the results showed something different. When he took the average of his data, it did not resemble the individual body size. There was no average hand size. And when he was working on the redesign, he kept asking himself:

How many pilots really were average?

So he decided to do another study. He took a sample size of 4,063 pilots. And this time, he made many categories with different average ranges. For example, your height could fall in a category like 1.60m — 1.75m, 1.75–1.85, etc. But this time the results failed him too — there was no average.

Out of 4,063 pilots, not a single man fit within the average range on all Daniels dimensions. One pilot might have a longer-than-average arm length, but a shorter-than-average leg length. Another pilot might have a big chest but small hips. So if you design a plane cockpit to fit the average, you might fit in no one. The opportunities are always at the extreme and not in the middle.

The tendency to think in terms of the ‘average man’ is a pitfall into which many persons blunder. It is virtually impossible to find an average airman not because of any unique traits in this group but because of the great variability of bodily dimensions which is characteristic of all men. Any system designed around the average person is doomed to fail — Daniels wrote in 1952.

Later on, people realised there is no average, and we should design for the extremes. After this type of study and conclusions, the aeronautical engineers of that time found solutions that were both cheap and easy to put in place. They designed adjustable seats, technology now standard in all cars. They created adjustable foot pedals, helmet straps and flight suits.

. . .

- Subscribe to our Magazine Newsletter.

- Follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn.

- Join our community on Slack and Facebook.

Start Prototyping

Get Started with Our Free, Web-Based Platform.

© Phase Software GmbH 2025